Node.js Event Loop: Phases, Queues, and Process Exit

As of Node.js 22 LTS (libuv 1.48.0), this article covers how Node schedules input/output (I/O): libuv phases first, then V8 (the JavaScript engine) microtasks and process.nextTick(), and finally process exit conditions. Includes a spec-precise contrast to the Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) event loop and the ECMAScript job queue.

Abstract

Mental model

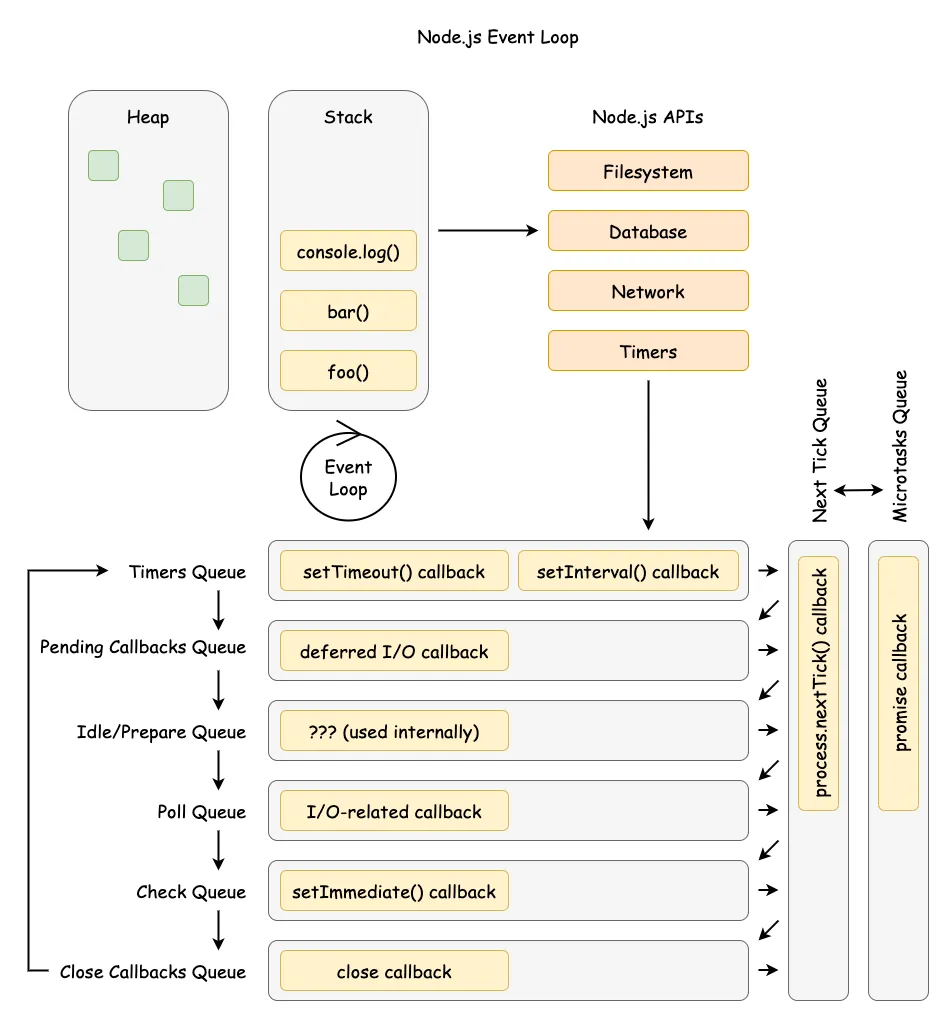

- The loop is a phased scheduler in libuv (Node’s cross-platform async I/O library): timers → pending callbacks → idle/prepare → poll → check → close callbacks.

- After each callback, Node drains

process.nextTick()and then the microtask queue (Promises andqueueMicrotask()). - The process exits when no ref’d handles or active requests remain.

Operational consequences

- The poll phase can block waiting for I/O readiness; recursive

process.nextTick()or microtask chains can starve I/O indefinitely. - Network I/O is non-blocking (epoll/kqueue/IOCP); file system operations,

dns.lookup(), crypto, and zlib use the libuv thread pool (default 4 threads, max 1024, shared process-wide). setImmediate()always fires before timers when called from an I/O callback; outside I/O callbacks, the order is non-deterministic.- Timers have millisecond resolution with ±0.5 ms jitter; they specify a minimum delay threshold, not a precise schedule.

Mental Model: Two Layers of Scheduling

Think of Node as two schedulers stacked together. The outer scheduler is libuv’s phased loop; the inner scheduler is the microtask and process.nextTick() queues owned by V8 and Node. A single “tick” is one pass through the phases; after each JavaScript callback (and before the loop continues), Node drains process.nextTick() and then microtasks.

Simplified flow (intentionally ignoring edge cases covered later):

- Pick the next phase in the fixed order and run its callbacks.

- After each callback, drain

process.nextTick(). - Drain microtasks (Promise reactions and

queueMicrotask()). - Repeat until no ref’d handles or active requests remain.

Example: A Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) server accepts a socket, runs the poll callback, schedules a Promise to update metrics, and calls setImmediate(). The callback runs, then process.nextTick(), then the Promise microtask, and the setImmediate() fires later in the check phase.

Phase Order and Semantics (libuv detail)

Node follows libuv’s six phases, each with its own callback queue. The order is fixed; what changes is how much work is queued in each phase and how long poll blocks.

“Each phase has a FIFO queue of callbacks to execute.” - Node.js Event Loop docs.

- timers: Executes expired

setTimeout()/setInterval()callbacks. - pending callbacks: Executes callbacks deferred from the previous loop iteration (for example, certain networking errors).

- idle, prepare: Internal libuv bookkeeping; no user-visible callbacks.

- poll: Pulls new I/O events from the operating system (OS) and runs their callbacks; may block if no timers are due.

- check: Executes

setImmediate()callbacks. - close callbacks: Handles

closeevents (for example, on sockets).

“A timer specifies the threshold after which a provided callback may be executed.” - Node.js Event Loop docs.

Timers are best-effort; operating system scheduling and other callbacks can delay them. libuv only supports millisecond resolution by rounding higher-precision clocks to integers—timers can be off by ±0.5 ms even in ideal conditions.

Breaking change in Node.js 20 (libuv 1.45.0): Prior to this version, libuv executed timers both before and after the poll phase. As of libuv 1.45.0, timers run only after poll. This changes how timers interleave with

setImmediate()in edge cases—code that relied on timers firing before I/O polling may behave differently. Node.js 22 LTS ships with libuv 1.48.0, which carries this behavior forward.

Repeating timers (setInterval) do not adjust for callback execution time. A 50 ms repeating timer whose callback takes 17 ms will reschedule after 33 ms, not 50 ms, because libuv rearms relative to its current idea of “now.”

Example: Schedule a 100 ms timeout, then start an fs.readFile() that finishes in 95 ms and runs a 10 ms callback. The timer fires around 105 ms, not 100 ms, because the callback delays the timers phase.

Microtasks and process.nextTick()

Node maintains two high-priority queues outside libuv’s phases: the process.nextTick() queue and the microtask queue.

“This queue is fully drained after the current operation on the JavaScript stack runs to completion and before the event loop is allowed to continue.” - Node.js

process.nextTick()docs.

“Within Node.js, every time the ‘next tick queue’ is drained, the microtask queue is drained immediately after.” - Node.js

process.nextTick()docs.

In CommonJS (CJS), process.nextTick() callbacks run before queueMicrotask() ones. In ECMAScript modules (ESM), module evaluation itself runs as a microtask, so microtasks can run before process.nextTick().

“This can create some bad situations because it allows you to “starve” your I/O by making recursive

process.nextTick()calls.” - Node.js Event Loop docs.

Ordering example from the Node.js queueMicrotask() vs process.nextTick() docs: (Node.js - process.nextTick() vs queueMicrotask())

const { nextTick } = require("node:process")Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log("resolve"))queueMicrotask(() => console.log("microtask"))nextTick(() => console.log("nextTick"))// Output (CJS):// nextTick// resolve// microtaskimport { nextTick } from "node:process"Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log("resolve"))queueMicrotask(() => console.log("microtask"))nextTick(() => console.log("nextTick"))// Output (ESM):// resolve// microtask// nextTickExample: A logging middleware that schedules itself with process.nextTick() can starve I/O if it creates an unbounded chain; use queueMicrotask() or setImmediate() when fairness matters more than immediate priority. Detection: Use monitorEventLoopDelay() from perf_hooks—consistent lag > 100 ms indicates starvation.

setImmediate() vs setTimeout() Determinism

The ordering of setImmediate() and setTimeout(..., 0) depends on context:

Inside an I/O callback (deterministic): setImmediate() always fires first because the loop is in the poll phase and proceeds directly to check before looping back to timers.

2 collapsed lines

const fs = require("node:fs")fs.readFile(__filename, () => { setTimeout(() => console.log("timeout"), 0) setImmediate(() => console.log("immediate"))})// Output: "immediate" then "timeout" (100% deterministic)Outside I/O callbacks (non-deterministic): Whether the timer or immediate fires first depends on process startup performance—if the loop enters the timers phase before the 1 ms minimum delay elapses, the timer fires first; otherwise, the immediate does.

setTimeout(() => console.log("timeout"), 0)setImmediate(() => console.log("immediate"))// Output order varies between runsDesign reasoning: setImmediate() exists specifically to schedule work immediately after I/O without waiting for timers. When predictability matters, prefer setImmediate() inside I/O callbacks or use explicit sequencing with Promises.

I/O Boundaries: Kernel Readiness vs. libuv Thread Pool

Network I/O is readiness-based and handled by the kernel with non-blocking sockets. libuv polls using platform mechanisms such as epoll (Linux), kqueue (macOS/BSD), event ports (SunOS), and I/O Completion Ports (IOCP, Windows), then runs callbacks on the event loop thread. By contrast, work that cannot be made non-blocking is pushed onto the libuv thread pool.

| Property | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Default size | 4 threads | Set at process startup |

| Maximum size | 1024 threads | Increased from 128 in libuv 1.30.0 |

| Configuration | UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE | Environment variable; must be set before process starts |

| Thread stack | 8 MB | Changed in libuv 1.45.0; was platform default (often too small for deeply nested code) |

| Thread naming | libuv-worker | Added in libuv 1.50.0 |

The thread pool services:

- File system operations: All

fs.*calls except those usingfs.watch()(which uses kernel notifications) - DNS lookups via

getaddrinfo:dns.lookup()anddns.lookupService()use the thread pool;dns.resolve*()performs network DNS queries and does not - Crypto operations:

crypto.pbkdf2(),crypto.scrypt(),crypto.randomBytes()(async),crypto.generateKeyPair() - Compression:

zlib.gzip(),zlib.gunzip(),zlib.deflate(),zlib.inflate()(async variants) - Custom work:

uv_queue_work()for user-specified tasks

Warning: The thread pool is not thread-safe for user data. While the pool itself is global and shared across all event loops, accessing shared data from worker threads requires explicit synchronization.

Example: A build tool that starts 1,000 parallel fs.readFile() calls will queue 996 tasks behind the 4-thread pool, inflating tail latency. Increasing UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE to 64 or 128 helps I/O throughput but increases memory usage and competes with central processing unit (CPU) time for the event loop.

Process Exit and Liveness

Node checks between iterations whether the loop is “alive.” The loop is alive if any of these conditions hold:

- Active and ref’d handles exist (timers, sockets, file watchers)

- Active requests are pending (I/O operations in flight)

- Closing handles are still in flight

When none of these conditions hold, the process exits. This is why short scripts terminate as soon as their last callback completes.

ref() and unref()

By default, all timers and immediates are ref’d—the process will not exit while they are active. Calling timeout.unref() allows the process to exit even if the timer is still pending; timeout.ref() reverses this. Both are idempotent. Use timeout.hasRef() to check current status.

const timeout = setTimeout(() => console.log("never runs"), 10000)timeout.unref() // Process exits immediately; timer does not keep it aliveExample: A background heartbeat timer that should not prevent graceful shutdown uses unref(). A critical timeout that must fire before exit uses ref() (the default).

Design reasoning: unref() exists because long-running servers often have background tasks (health checks, metrics flushing) that should not block shutdown. Without unref(), you would need to manually clear every timer during shutdown.

Browser Event Loop Contrast (Spec-precise)

The HTML event loop model is similar in spirit but not identical in mechanism. The spec explicitly separates task queues from the microtask queue:

“Task queues are sets, not queues.” - Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) Standard, “Event loop processing model”.

“The microtask queue is not a task queue.” - Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) Standard, “Event loop processing model”.

The spec also preserves ordering within a single task source:

“the user agent would never process events from any one task source out of order.” - Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) Standard, “Event loop processing model”.

ECMAScript specifies job queues as FIFO queues:

“A Job Queue is a FIFO queue of PendingJob records.” - ECMAScript Language Specification, “Jobs and Job Queues”.

Net effect: because task queues are sets and the user agent selects a runnable task from a chosen queue, ordering across different HTML task sources is not guaranteed, but ordering within a given source is. Node’s fixed phase order and its extra process.nextTick() queue make scheduling more predictable for server workloads but easier to starve if high-priority queues are abused.

Example: In a browser, a user input task can run before a timer task depending on task source selection; in Node, an I/O callback and a setImmediate() follow the poll -> check phase order.

Conclusion

Node’s event loop is a deliberate trade-off: fixed phases and a dedicated thread pool make I/O-heavy servers predictable and scalable, while the high-priority queues (process.nextTick() and microtasks) offer low-latency scheduling at the cost of potential starvation. The libuv 1.45.0 timer change (Node.js 20+) affects edge cases around timer/immediate ordering, and the CJS vs ESM microtask ordering difference can cause subtle bugs when porting code.

Use the simplified two-scheduler mental model to reason quickly, then drop to the phase-level view when debugging ordering and latency. When in doubt, prefer setImmediate() inside I/O callbacks for deterministic scheduling and queueMicrotask() over process.nextTick() for portability.

Appendix

Prerequisites

- Familiarity with Promises, timers, and non-blocking I/O in Node.js.

Terminology

- Tick: One pass through the libuv phases.

- Phase: A libuv stage that owns a callback queue (timers, poll, check, etc.).

- Handle: A long-lived libuv resource (timer, socket, file watcher) that keeps the event loop alive while active and ref’d.

- Request: A short-lived libuv operation (write, DNS lookup) that keeps the loop alive while pending.

- Task: A unit of work scheduled onto an HTML task queue (browser concept).

- Task source: A category of tasks in HTML (for example, timers, user interaction, networking).

- Microtask: A high-priority job processed after tasks/phases (Promises,

queueMicrotask()).

Summary

- libuv executes callbacks in fixed phases; Node drains

process.nextTick()then microtasks after each callback. - Timers have millisecond resolution with ±0.5 ms jitter; they specify a minimum delay threshold, not a precise schedule.

- Since Node.js 20 (libuv 1.45.0), timers execute only after the poll phase—a breaking change from prior versions.

- The libuv thread pool (default 4, max 1024 threads) services fs, dns.lookup(), crypto, and zlib; it can bottleneck I/O-heavy workloads.

setImmediate()always fires before timers inside I/O callbacks; outside them, the order is non-deterministic.- The process exits when no ref’d handles or active requests remain; use

unref()for background timers that should not block shutdown. - HTML and ECMAScript specs model tasks and microtasks differently from Node’s phase-based loop.

References

- HTML Standard - Event loop processing model

- ECMAScript 2015 Language Specification (ECMA-262 6th Edition) - Jobs and Job Queues

- libuv - Design overview

- libuv - Thread pool work scheduling

- libuv - Timer handle

- Node.js - The Node.js Event Loop

- Node.js - Understanding

process.nextTick() - Node.js -

process.nextTick()API - Node.js -

process.nextTick()vsqueueMicrotask() - Node.js - Timers API

- Node.js - DNS module

- Node.js - Performance measurement APIs (

monitorEventLoopDelay)

Read more

-

Previous

libuv Internals: Event Loop and Async I/O

Browser & Runtime Internals / JavaScript Runtime Internals 36 min readExplore libuv’s event loop architecture, asynchronous I/O capabilities, thread pool management, and how it enables Node.js’s non-blocking, event-driven programming model.

-

Next

JS Event Loop: Tasks, Microtasks, and Rendering (For Browser & Node.js)

Browser & Runtime Internals / JavaScript Runtime Internals 17 min readThe event loop is not a JavaScript language feature—it is the host environment’s mechanism for orchestrating asynchronous operations around the engine’s single-threaded execution. Browsers implement the WHATWG HTML Standard processing model optimized for UI responsiveness (60 frames per second, ~16.7ms budgets). Node.js implements a phased architecture via libuv, optimized for high-throughput I/O (Input/Output). Understanding both models is essential for debugging timing issues, avoiding starvation, and choosing the right scheduling primitive.